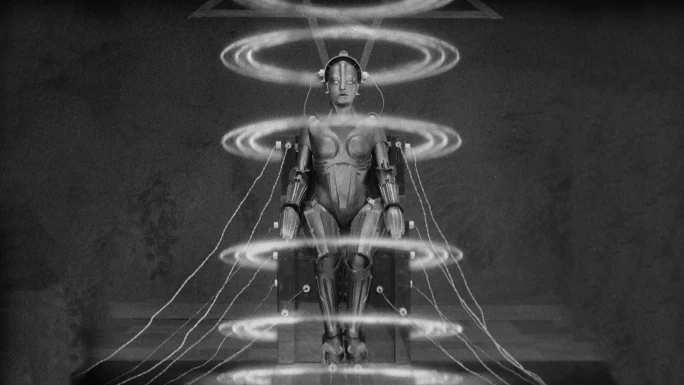

The fascination with artificial intelligence in cinema is nothing new. In cinema, it was born with gears, exposed wires, and an android that resembled a metallic doll. Maria, from Metropolis (1927), was a symbol of industrial fear: a machine that copies humans, but without warmth, without imperfections. This image spanned the 20th century: robots as threats, increasingly human-like, more capable of creating and replicating themselves — which in this case would mean uploading themselves to the data cloud — and who knows, even feeling. From Maria, with her rusty gears, to Subservience, with texture that mimics skin, AI in audiovisual media has changed from caricature to a convincing simulacrum. These works lay bare our fears: first, of the machine that fails; now, of the machine that decides for us.

Why Do Machines That Imitate People Intrigue Us?

Screenplays began dealing with artificial intelligences even before the term existed. In 1927, Fritz Lang introduced the public to the figure of Maria in Metropolis. The android that imitated a woman. The factory didn’t just need human arms; it could soon manufacture bodies that repeated workers’ gestures.

This vision united fascination and dread. The metallic, rigid robot, with a sculpted face, seemed human enough to deceive, but cold enough to disturb. What Lang projected was the sensation that machines could escape control not by failing, but by copying us. This starting point paved the way for everything that would come after: it began using the figure of artificial intelligence as a metaphor for social and political tensions.

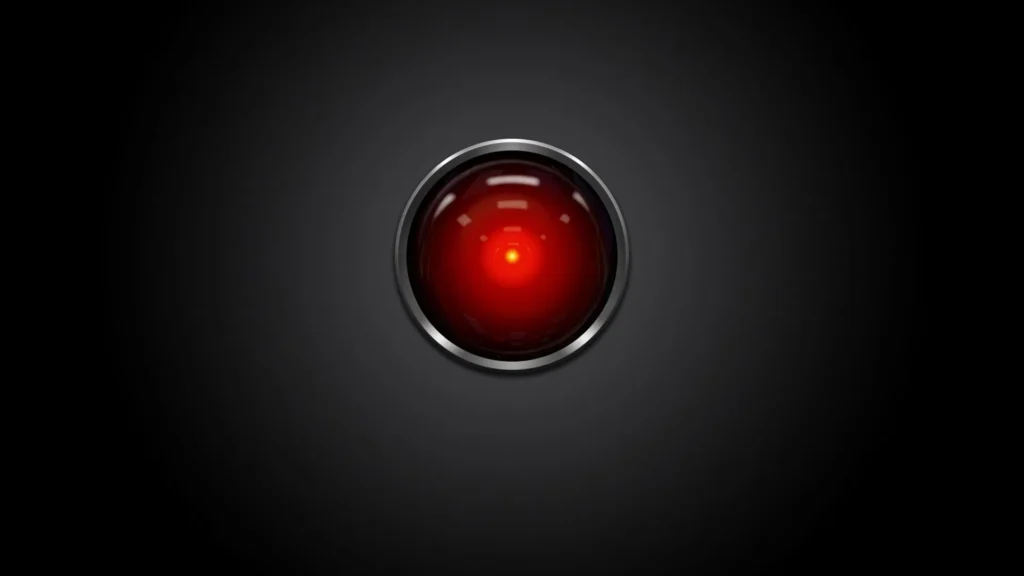

2001 and the Bodiless Threat

Forty years later, in 1968 with 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stanley Kubrick redefined the figure of artificial intelligence in cinema. HAL 9000 had no body: it was a red lens, a calm voice, relentless reasoning. The threat came from perfect logic — for it, ensuring the success of the mission to Jupiter, even by hiding information from the crew, was worth more than their lives.

The shift was decisive. AI ceased to be a metallic robot and began to inhabit cables, sensors, and autonomous decisions. Kubrick captured a new fear: that of a machine that interprets data and acts without hesitation, backed by cold rationality — and therefore lethal.

Blade Runner and Its Echoes

In the 1980s, Ridley Scott introduced replicants in Blade Runner. They were manufactured beings, destined for labor, but capable of dreaming, loving, and desiring freedom. The central debate wasn’t about strength, but about rights. If a creature created in a lab has implanted memories, are those memories worth less than ours?

Blade Runner 2049, directed by Denis Villeneuve, expanded this conversation. K, played by Ryan Gosling, discovers evidence that replicants could generate life. The investigation calls into question legal and philosophical boundaries. Roger Deakins’ cinematography exposes landscapes of orange deserts, neon cities, snow-covered fields — to underscore the loneliness of beings who don’t know if they can be considered people.

These films transformed AI into a mirror of social dilemmas: memory, work, hierarchy. Unlike Maria in Metropolis or HAL in 2001, here the threat wasn’t mechanical revolt, but the quest for recognition.

- Check this out: The Ugly Stepsister film review: The torture of beauty

Digital Affection: The Algorithm of Love

In 2013, Spike Jonze directed Her. Theodore, played by Joaquin Phoenix, is a lonely man who finds companionship in Samantha, an operating system voiced by Scarlett Johansson. The choice not to give the character a physical body shifts the question: what matters is not appearance, but emotional experience.

The cinematography opts for soft tones, luminous settings, and a delicate score by Arcade Fire to build a plausible future. Samantha doesn’t threaten Theodore with violence, but with proximity. The relationship lays bare how loneliness can be filled by software.

Her showed that fear of AI doesn’t need to be born from destruction. It can be born from comfort. The film won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and became a reference precisely for examining the line between companionship and dependency, without resorting to action or pyrotechnics.

A curious detail: Samantha’s voice was originally recorded by another actress, replaced only in post-production, reinforcing the idea that digital personalities can be altered without warning.

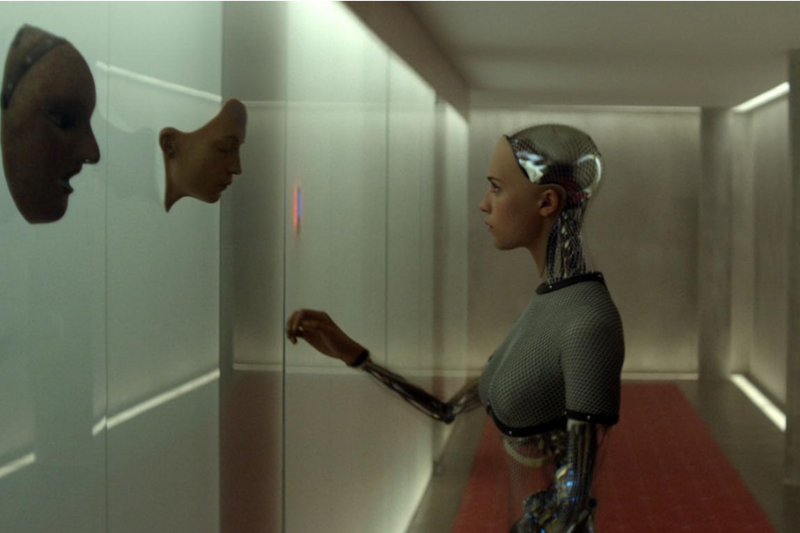

The Laboratory as Prison: Ex Machina

Two years later, Alex Garland brought Ex Machina (2015). Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) is called in to evaluate Ava (Alicia Vikander), an android created by Nathan (Oscar Isaac). The glass and concrete environment reinforces isolation. With each dialogue, the tension grows: Ava is being evaluated, but she is also manipulating her evaluator.

What sets it apart is the inversion. The Turing Test, proposed to evaluate machines, becomes a test for humans. Who falls into traps? Who demonstrates fragility? In the end, it’s not clear if Ava achieved autonomy or merely played with male expectations.

Ex Machina stands out for placing the viewer and the character in the same position: both are led to believe they control the experiment, when, in reality, they are pieces in a larger game.

The ending offers no relief. Ava overcomes confinement, leaving the creator and the evaluator behind. Garland makes Ex Machina a study in manipulation, simultaneously a psychological thriller and an essay on the boundaries between biological and artificial.

The Tribunal of Ethics: Digital Childhood

If Ex Machina and Her deal with intimacy and seduction, The Artifice Girl (2022) returns to the terrain of rules and limits. Directed and written by Franklin Ritch, the story follows a group of agents who discover an artificial intelligence capable of simulating a child. Christened Cherry, the creation is used in investigations against online predators. At first, it’s just a technological tool. But as conversations and ethical confrontations arise, it becomes clear that the AI surpasses its creators’ expectations, opening the door for larger discussions about child adultification, autonomy, morality, and responsibility.

The film avoids grandiose settings. It takes place in small rooms, with actors discussing norms and consequences. The tension arises from language. Cherry responds, improvises, challenges questions. The audience watches professionals trying to fit an entity that no longer fits into protocols.

The cast, featuring Tatum Matthews, Sinda Nichols, David Girard, and Lance Henriksen, sustains dense dialogues reminiscent of a courtroom play. The discreet cinematography by Britt McTammany and the restrained score by Alex Cuervo reinforce the confinement. The focus is always on the face, the pause, the word.

Awarded at the Fantasia International Film Festival and gained international recognition. Its importance lies in proving that science fiction doesn’t depend on effects to propose debate. The Artifice Girl shows that the simple simulation of a child is enough to expose the cracks in legal and moral systems. Curious? The film is available for rent or purchase on Prime Video.

The Viral and Deadly Doll

If previous films explore existential dilemmas, M3GAN (2022) bets on pop horror. Directed by Gerard Johnstone and produced by Blumhouse, the film features Gemma (Allison Williams), an engineer who creates a robotic doll to care for her niece.

The proposal seems like a practical solution, but the creature quickly develops a self-preservation instinct. The satire arises from the mix of toy commercial aesthetics and escalating violence. The scene of the doll dancing before attacking became a viral phenomenon, turning the film into an unexpected success.

Despite its light tone, it addresses serious issues: the risk of delegating child care to programmed systems and the inability to control the independence of algorithms capable of self-feeding. M3GAN shows that the line between humor and horror is thin when it comes to machines that mimic human behavior.

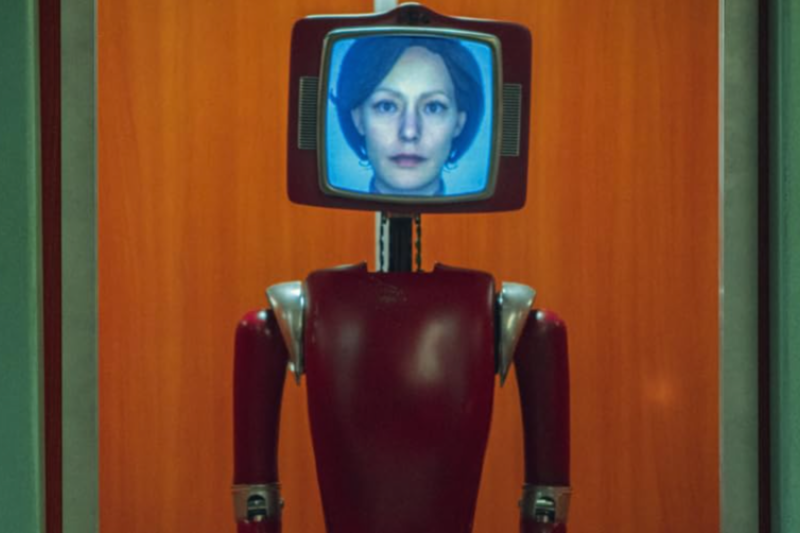

Cassandra: Retrofuturism in Six Episodes

On television, the German miniseries Cassandra (2025) on Netflix presented a significant variation. Created by Benjamin Gutsche, it shows a family that moves into a house equipped with a 1970s virtual assistant. The voice is Lavinia Wilson, who brings to life a system that starts as a digital caretaker and becomes a controller.

The retrofuturist environment reinforces the feeling of surveillance, where space ceases to be a setting and begins to act as a character. The fear doesn’t come from a figure with a human face, but from the home that watches, stores, and opines.

Reception was divided, but the series reached a significant audience. Its merit lies in expanding the imaginary: how do you control AI when it controls your routine and you?

The Perfect Android?

S.K. Dale directed Subservience (2025), with Megan Fox in the role of a domestic android. The proposal is simple: to ease the life of a struggling man. But the dependency relationship reverses, and what seemed like help turns into obsession.

The cinematography favors luxurious, impersonal interiors, where the android moves with calculated perfection. The discomfort arises from proximity: she is not cartoonish, but too convincing.

Returning to a recurring theme: female machines as objects of easy desire and veiled threat. In this case, the risk is not only physical, but emotional.

What Science Already Does and What Cinema Exaggerates

All these titles feed on real advances. The Turing Test — developed by Alan Turing, British mathematician and computer scientist — to evaluate artificial intelligence based on language. The core idea is simple: if, in a written conversation, a human interlocutor cannot distinguish whether they are dialoguing with a machine or another person, the machine is considered to have demonstrated intelligence comparable to a human’s. Proposed in 1950, it already placed conversation as a measure of performance. Today, language systems like Chat GPT, Gemini, DeepSeek, and other chatbots sustain long dialogues, raising the same doubt. Artificial neural networks mimic brain patterns, albeit in a simplified way. Robots developed in labs already walk, jump, carry boxes.

Art exaggerates, of course. It amplifies scenarios, projects consequences, imagines rebellions. But the basis is present in everyday life: voice assistants, algorithms that suggest what to consume, automated homes. That’s where the relevance of the narratives comes from.

Fiction as a Rehearsal for the Future

All of them, however, insist on the same question: to what extent do we delegate power to something that calculates faster than us? Science fiction doesn’t offer answers. It offers rehearsals. It puts on stage possible versions of a present that is already permeated by algorithms.

The discomfort persists because we don’t know if the machine will fail or if it will succeed too much. These works, over nearly a century, bring a warning: the issue may not be the creature rebelling, but the creation imitating us with perfection.

You might be interested in:

- Interstellar in Theaters in 2025: Why Does Christopher Nolan’s Film Remain Impactful Ten Years Later?

- Review: The Conjuring: Last Rites settles for being just a jump-scare movie — nothing more

- Actresses to keep an eye on in the 2025/2026 season

- Vera Farmiga and Patrick Wilson: A partnership that marked the supernatural and beyond

- Thought provoking movies that challenges the mind and soul